European Parliament approves PNR agreement with the US. What’s next?

[MEPs picket outside the plenary chamber to ask their colleagues to say “No” to the PNR agreement with the US. (Photo by greensefa, some rights reserved under Creative Commons license, CC BY 2.0)”]

[MEPs picket outside the plenary chamber to ask their colleagues to say “No” to the PNR agreement with the US. (Photo by greensefa, some rights reserved under Creative Commons license, CC BY 2.0)”]

Last week — despite the demonstration shown above (more photos here) by Members of the European Parliament as their colleagues entered the plenary chamber for the vote — the European Parliament acquiesced, reluctantly, to an agreement with the US Department of Homeland Security to allow airlines that do business in the EU to give the DHS access to PNR (Passenger Name Record) data contained in their customers’ reservations for flights to or from the USA. (See our FAQ: Transfers of PNR Data from the European Union to the USA.)

The vote is a setback for civil liberties and the the fundamental right to freedom of movement, in both the US and Europe.

But the vote in the European Parliament is neither the definitive authorization for travel surveillance and control, nor the full grant of retroactive immunity for travel companies that have been violating EU data protection rules, that the DHS and its European allies had hoped for.

Many MEPs voted for the agreement only reluctantly, in the belief (mistaken, we believe), that it was “better than nothing” and represented an attempt to bring the illegal US surveillance of European travelers under some semblance of legal control.

Whatever MEPs intended, the vote in Strasbourg will not put an end to challenges to government access to airline reservations and other travel records, whether in European courts, European legislatures, or — most importantly — through public defiance, noncooperation, and other protests and direct action.

By its own explicit terms, and because it is not a treaty and is not enforceable in US courts, the “executive agreement” on access to PNR data provides no protection for travelers’ rights.

The intent of the US government in negotiating and lobbying for approval of the agreement was not to protect travelers or prevent terrorism, but to provide legal immunity for airlines and other travel companies — both US and European — that have been violating EU laws by transferring PNR data from the EU to countries like the US. The DHS made this explicit in testimony to Congress in October 2011:

To protect U.S. industry partners from unreasonable lawsuits, as well as to reassure our allies, DHS has entered into these negotiations.

But because of the nature of the PNR data ecosystem and the pathways by which the DHS (and other government agencies and third parties outside the EU) can obtain access to PNR data, the agreement does not provide travel companies with the full immunity they had sought.

Most of the the routine practices of airlines and travel companies in handling PNR data collected in the EU remain in violation of EU data protection law and subject to enforcement action by EU data protection authorities and private lawsuits by travelers against airlines, travel agencies, tour operators, and CRS companies in European courts.

Why is that?

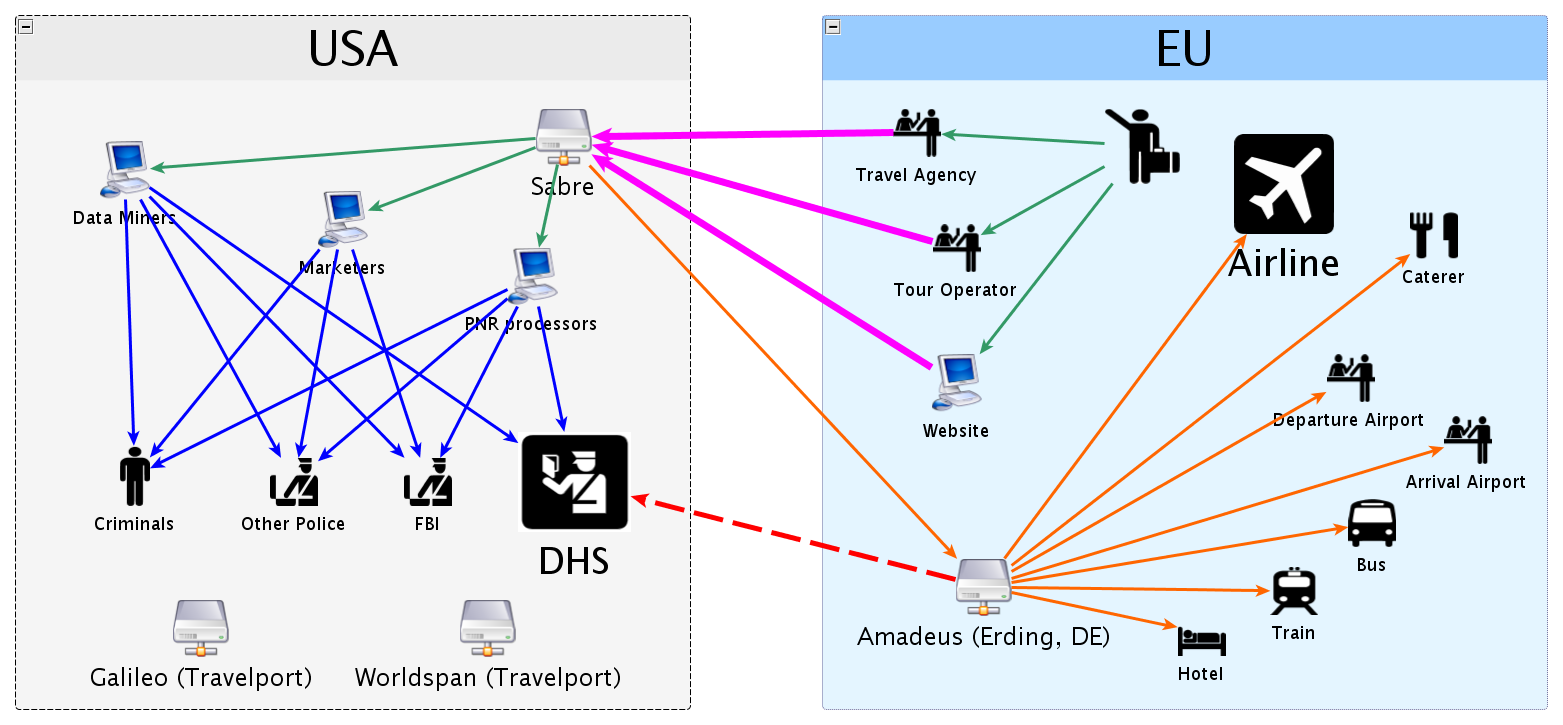

As we discussed in an interview with the French newspaper Le Monde published after the vote on the PNR agreement (“Les boîtes noires de l’accord sur les données passagers“), the central role in storing and transmitting PNR data across borders in played by computerized reservation systems (CRSs) that serve as outsourced database hosting and connectivity providers for airlines, travel agencies, tour operators, and other travel companies.

The EU-US agreement only regulates transfers of PNR data from airlines to the DHS. But few airlines host their own PNR databases or transfer data directly to the DHS. Because most of the CRSs are based in the US, PNR data is typically available to the DHS and a wide range of other commercial and governmental entities through US-based CRSs and data pathways that are not regulated by the EU-US agreement.

In the diagram below from our testimony to Members of the European Parliament in Brussels in 2010, only PNR data transfers represented by the dotted red line would be regulated by the EU-US agreement. All of the other lines on the diagram represent PNR data transfers that are neither regulated nor legalized by the agreement, and which remain subject to (and in violation of) existing EU data protection rules:

[The central place of CRSs in the PNR ecosystem. (Click image for details.)]

[The central place of CRSs in the PNR ecosystem. (Click image for details.)]

The DHS has known for years that European PNR data was routinely being stored by CRSs in the US, and could be obtained without the knowledge or consent of European travel companies or travelers. In a secret 2006 cable from the U.S. Embassy in Berlin to Washington about the status of the PNR negotiations, later made public by Wikileaks, Assistant Secretary (”A/S”) of Homeland Security Stewart Baker — the chief drafter and negotiator of the earlier versions of the PNR agreement — reported as follows on his discussions with the German government:

A/S Baker warned that in many cases the actual airline databases reside in the United States, and the airlines of many EU countries do not have flights to the United States, and so in this light, from the U.S. perspective, it was difficult to see why an EU government and parliament should have any influence on the access of U.S. agencies to data in the United States.

In light of statements like this, the US can’t now claim to be surprised if outsourcing of PNR storage by travel companies in Europe to CRSs in the US, where the data is freely (and secretly) available to the DHS and others, is found to violate existing EU data protection rules on commercial cross-border data transfers.

Even the one major CRS based in Europe, Amadeus, has offices in the US (and other countries around the world, from China and Saudi Arabia to Israel and Nigeria) with access to all Amadeus PNRs.

MEPs have begun asking questions, as they should, about whether CRSs are complying with EU law. Unfortunately, the responses to these questions to date have been evasive and have contradicted what travel companies have said in response to travelers’ requests for information about themselves.

One of the most important discrepancies concerns whether Amadeus, other CRSs, or the DHS keep access logs for PNR data. We have seen no evidence that they do, and whenever travelers have requested the logs of access to their PNR data, CRSs and the DHS have said that no such logs exist.

Without records of what CRSs have done with PNR data, and to whom they have disclosed it, it will be impossible for anyone to police their activities.

The latest response from the European Commission claims that “Amadeus keeps logs of all transfers of PNR to the US authorities for specific periods of time, which vary depending on the type of transfer. Therefore, it is possible to trace back what data were transferred and when.” However, in response to one of our requests for these logs, KLM (which stores its PNRs in the Amadeus system), told the Dutch Data Protection Authority:

[T]he only information Amadeus can see regarding PNR communication with US-CBP is that there is communication with US-CBP. This means that they are not able to see what is in the communicated dataset. Based on the volume of the message they can safely assume that it concerns either a PNR or a Flight Manifest (but not which PNR or Flight number).

Who is telling the truth about whether Amadeus keeps logs of what PNR data is accessed by CBP/DHS? Should we believe the European Commission? Or should we believe an airline, KLM, that stores all its data in the Amadeus system and relies on Amadeus as its single most important IT services outsourcing provider?

As for any access logs kept by CBP (the division of DHS that accesses PNR data), the agency has continued to insist, in response to our lawsuit, that they are unable to produce any “accounting of disclosures” showing which other agencies or third parties have received our PNR data, because no such logs exist. We are continuing to seek further clarification from CBP about their record-keeping, in the course of negotiations about the remaining unresolved issues in our lawsuit.

In the meantime, travelers can, and should, continue to request their travel records from airlines, travel agencies, tour operators, and any CRSs they can identify, and pursue complaints with European authorities or lawsuits in European courts if they don’t receive a full accounting of where and to whom their data has been transferred, or if their data has been “outsourced” to the USA without their knowledge or consent.

CRS practices should also be an important issue in the current review of the 1995 EU Data Protection Directive. The European Commission has proposed a package of new measures to replace that directive, and the European Parliament is just beginning its consideration of those proposals.

Now that PNR data and other travel records have come to be recognized as among the most significant and sensitive categories of personal information, and CRSs are beginning to be recognized as key outsourced and offshore data warehousing and data mining companies, it’s critical to make sure that the evaluation of these general data protection proposals includes a specific evaluation of how they would apply to CRSs and whether they would provide adequate protection for PNR data.

A fig leaf of legality and data protection for commercial transfers of personal data from the EU to companies in the US is currently provided by the so-called Safe Harbor self-certification framework. As the US government describes it, “Any U.S. organization that is subject to the jurisdiction of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) or U.S. air carriers and ticket agents subject to the jurisdiction of the Department of Transportation (DoT) may participate in the Safe Harbor.”

Most of the attention to Safe Harbor enforcement has been directed at the FTC. But the FTC has no jurisdiction whatsoever over airlines travel agencies, or (we’ve been told recently by high-level FTC staff) over CRSs. Any enforcement of the Safe Harbor privacy protection rules, as they apply to these travel companies, could only be undertaken by the DOT.

In a letter sent to the European Commission at the request of the FTC, and included within the Safe Harbor decision as Annex VI, the DOT promised that it would “give … a high priority” to investigation and prosecution of false claims by airlines or other companies under DOT jurisdiction to comply with the Safe Harbor principles. Unfortunately, that hasn’t happened. So far as we can tell, the DOT has used its jurisdiction only to block other agencies like the FTC from protecting travelers’ privacy. So far as we can tell, the DOT has never initiated a Safe Harbor investigation on its own initiative, or any prosecution, and has dismissed the only formal third-party privacy complaint brought before it on the grounds that the privacy violations by the airline, while egregious, did not violate any US law.

As part of its consideration of Safe Harbor and the current EU data protection proposals, the European Parliament should demand an explanation, directly from the responsible DOT officials, for their complete failure to police or enforce Safe Harbor violations by airlines, travel agencies, and CRSs. Unless something changes at the DOT, the EU finding that the Safe Harbor framework provides an “adequate” level of protection for data transferred to travel companies under DOT jurisdiction should be withdrawn.

As we noted in our most recent testimony to the European Parliament in 2011, the global CRS cloud already exemplifies — and has for more than 20 years — the jurisdictional and other data protection problems of personal data stored by cloud services. Those issues will only be exacerbated as Google and other new global cloud service providers begin offering outsourced PNR hosting and other CRS services.

Proposals for protection of data stored in the cloud should be tested and evaluated as to whether they would effectively ameliorate the current severe privacy and data protection problems with PNR data stored in the CRS cloud. Because the CRS cloud was the first and for decades was the largest global real-time aggregated multi-company global commercial cloud data service, no meaningful discussion of cloud services can be conducted without including specific consideration of the lessons of the CRS and PNR data experience.

The EU-US agreement, like the amendments made to Canada’s privacy law (PIPEDA) to authorize transfers to the DHS of PNR data collected in Canada, only authorizes DHS access to PNR data for flights to, from, or via the USA. But the DHS is already accessing passenger data beyond the scope of these permissions, creating potential liability for the travel companies that have allowed this access.

The details of what data airlines have been ordered to make available, and for what flights, are contained in secret “Security Directives” from the DHS to airlines that are exempt from the US Freedom of Information Act. But it appears that the DHS has first extended its Secure Flight program to flights that are scheduled to overfly the US, and then to flights that aren’t scheduled to overfly or land in the US, but that might be diverted to or over the US in the event of an emergency. That reportedly includes all flights to or from some Canadian cities close to the US border, including Montreal and Toronto.

Our guess is that the DHS has told airlines that their planes won’t be allowed to enter US airspace — even in an emergency — unless Secure Flight Passenger Data was provided to the US in advance. Those asked to provide Secure Flight data for flights that aren’t scheduled to land in or overfly the US are entitled by Canadian and EU laws to decline to provide this information and decline to consent to it being made available to US authorities.

DHS “advisors” stationed at airports in Europe and around the world are also being given access to PNR data — it’s unclear on what, if any, legal basis — which they are using to make no-fly “recommendations” to airlines. According to the same October 2011 DHS testimony to Congress we quoted from above:

CBP stations Immigration Advisory Program (IAP) officers at certain foreign airports…. At the invitation of foreign partners, IAP officers make ”no-board” recommendations to airlines on the basis of passenger data analysis and a review of individual travel documents…. CBP’s National Targeting Center-Passenger (NTC-P) analyzes PNR data received up to 72 hours prior to departure and provides recommendations to the IAP officers…. IAP officers are currently posted at ten airports in eight countries, and have recommended, in part based upon PNR data, a total of 2,875 no-boards in fiscal year 2011, including nine No-Fly hits, 74 confirmed Terrorist Screening Database matches, and 109 cases of fraudulent document use.

This may have been what happened to Jennifer Robinson, an Australian human rights lawyer who was delayed checking in a Virgin Atlantic flight from London Heathrow back home to Australia after an interview with her client Julian Assange of Wikileaks. Ms. Robinson was told her travel was “inhibited”, which is the middle of three “risk scores” assigned under the Secure Flight system, and describes someone deemd to require further investigation before a fly/no-fly permission decision is made. As an Australian citizen, Ms. Robinson’s right to leave the UK and return to the country of her citizenship was guaranteed by Article 12 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, as ratified by the UK, Australia — and the US.

Was it the DHS “advisors” at Heathrow who (illegally) “inhibited” Ms. Robinson’s check-in, or “recommended” that the airline inhibit her form leaving the country or returning home? Since she was eventually allowed to check in and board, without missing her flight, we’ll probably never know.

What is the legal basis for “no-board” decisions made on the basis of DHS “recommendations”? We’ll only find out if those who are denied boarding sue the airlines in European, Canadian, or other non-US courts.

Much of the debate about PNR data has focused on its use for monitoring of travelers’ movement. But as the DHS testimony quoted above makes clear, this isn’t just passive surveillance. PNR data is also one of the inputs to the “black box” of fly/no-fly decision-making. Nothing in the EU-US agreement addresses how PNR data is used, legalizes no-fly decisions that would otherwise violate European, US, or international law, or gives airlines that fail to fulfill their duties as “common carriers” any immunity from lawsuit.

That’s been clarified and reinforced by the recent European Parliament resolution of 29 March 2012 on the functioning and application of established rights of people travelling by air (2011/2150(INI)), which includes the following:

The European Parliament…

Whereas the most important passenger right is the right to services provided as scheduled, based on the fundamental right to freedom of movement and the contractual obligation which arises from selling a ticket;…

19. Underlines that passengers should have full access to information about their “Passenger Name Record” (PNR) data and be informed of how their PNR data are used and with whom they are shared; considers also that, with a view to guaranteeing passengers’ right to privacy, the air carrier may only require PNR data from passengers when necessary and proportional in connection with the ticket reservation, and stresses that passengers should not be denied the right to transport, except if the boarding denial is requested by the competent authority in justified cases for public security reasons and if it is explained to the passenger by the competent authority and confirmed in writing;

20. Emphasises that, if a passenger who has already boarded is asked to leave the aircraft because of his PNR, disembarkation must be carried out by the competent authorities and not by members of the crew;

It will be interested to see how European airlines, and other airlines operating from European airports implement these principles — or what happens if they don’t, and those denied boarding sue them.

The bottom line is that the PNR controversy, even in Europe, is far from over.

Scary stuff. When I first began traveling full time, I never imagined there would be a time in the US when you’d need to have papers…and as a white guy I still pretty much am free to go anywhere in the lower 48 as I wish…but obviously that’s not true in a lot of places for anyone who even looks a tad bit hispanic or Mexican. And who would have thought we’d ever need a passport to get into Canada?

We’ve avoided the great northern hat of America ever since passports were required…which is our fault, I know, as we’re legal residents and all…but something about it just doesn’t sit well. It’s bad enough going through border partrol in Texas & Arizona, where at least the way we look gets us through pretty quickly, but as for the northern border, well “our looks” actually play a reverse role there…

anyway, thanks for the blog, look forward to reading more.

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » How the NSA obtains and uses airline reservations

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » TSA’s lying “response” to today’s story in the New York Times

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » Trump repudiates agreement with EU on PNR data

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » Muslim Ban 3.0 blaimed on ICAO passport standards and “ID management”

Pingback: European high court to review PNR-based travel surveillance – Papers, Please!

Pingback: European court (again) finds US data protection inadequate – Papers, Please!

Pingback: FBI enlists reservation services to spy on travelers – Papers, Please!