FBI wants records from travel data aggregators

Ryan Singel of Wired News has reported that documents (see the links to some of them at the end of the Wired story) provided in response to requests under the Freedom of Information Act show that the FBI’s National Security Branch “National Security Analysis Center” (NSAC) has obtained a variety of commercial travel records from hotel chains and franchisers, car rental companies, and the operator of the financial clearinghouse for most airline tickets (and some other travel services) issued or sold by travel agents in the USA.

The numbers of these records Wired reports that the FBI has already obtained are small compared to the numbers of customers these companies have, but Wired also reports that the FBI documents they obtained also show that the FBI is seeking, as part of a lengthy “wish list” of data types and sources, to get greater and perhaps routine and comprehensive access to these travel records.

Given the lax rules for inter-agency data sharing, and the FBI’s lead role in the inter-agency “Terrorist Screening Center” where no-fly decisions enforced by the TSA are made, it’s less important which specific federal agency has or is seeking this data than what information they are after, and from whom.

The key player named in the documents cited by Wired is the Airlines Reporting Corporation (ARC), a closely-held company owned by USA-based and foreign airlines. When a travel agent or agency in the USA issues a ticket, they include the details of the ticket, and the amount owed by the agent to the airline if the customer has paid the agent, or the amount to be charged by the airline to the customer’s credit card, in a daily electronic report to ARC. ARC takes the daily total out of the agent’s bank account, and distributes the money and the ticketing and credit card charge data to the “validating” (issuing) airlines, based on the information in the agent’s ARC report. ARC acts as an intermediary between travel agents in the USA and airlines based in the USA and other countries around the world, including a fair number that don’t fly to the USA at all. (Travel agents in other countries, including Canada, use a parallel “Billing and Settlement Plan” (BSP). But the BSP is operated through regionally-designated “area banks” rather than through a special-purpose entity comparable to the ARC.)

What information does the ARC have? Why would the FBI — or any U.S. government agency — want this data? Why would they be particularly interested in getting it from ARC, rather than from alternative sources (such as directly from travel agencies or airlines, or from other intermediaries or aggregators)? And what issues does government access to ARC data raise?

Almost all travel agencies generate their ARC reports from Passenger Name Records (PNRs) stored by the travel agency in the Computerized Reservation System (CRS) or CRSs to which the agency subscribes. (The CRSs themselves make this data available on the Web, without a password, to anyone who shoulder-surfs a last name and record locator off a ticket or itinerary, picks a discarded boarding pass out of the trash, or reads the tag on a piece of luggage going around on the baggage-claim carousel, as though checking to make sure it’s their own before taking it.) But ARC doesn’t receive the entire PNR, only the ticketing and payment information. That would seem to give the government, or any third party, an interest in getting the data from a source that could provide full PNRs.

But ARC data, or data from other aggregators, offers the FBI or other would-be travel snoops two advantages: (1) normalization, and (2) lesser risk of liability for violations of U.S. wiretapping or foreign privacy and data protection laws. Since 9/11, the government has had an intense interest in airline data aggregators, with the FBI in particular (although also, of course, the DHS) repeatedly using them as a channel through which to get data for airline passenger surveillance, profiling, and control.

Travel agencies — even those that use the same CRS — use widely varying procedures and enter data in widely varying ways. The same information can be entered in different fields of the PNR, and can be encoded in ways that make it extremely difficult even to recognize it as pertaining to the same attribute. Someone who wants to mine travel data wants it predigested, so that they can search the universe of airlines and travelers with a single query against a single data set.

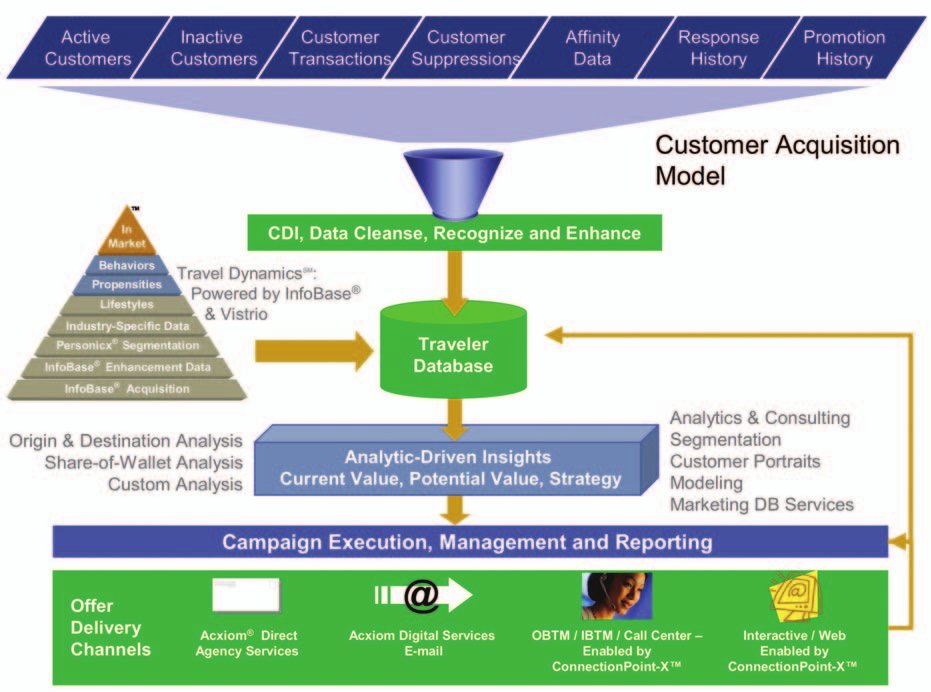

Despite major similarities dictated by competition and the need to fulfill the same business needs, the differences between the four major CRSs make it a significant challenge to merge PNR data from multiple CRSs into a common database. Only two companies, both wholly or partially owned by CRSs, currently attempt to do this on a commercial scale. For many years this niche has been overwhelmingly dominated by Airline Automation, Inc. (now a US-based division of the Europe-based Amadeus CRS), which contracts with airlines to provide multi-CRS PNR processing for airlines’ own use in pricing. Airline Automation reports are used by airlines, for example, to track trends in things like how far in advance of travel what percentages of tickets on particular routes are issued at which prices. More recently, Vistrio — a joint venture of the Sabre CRS and the Equitec division of data aggregation, mining, and profiling company Acxiom, with the tag-line to its corporate customers, “You Can’t Tell Where They’re Going If You Don’t Know Where They’ve Been” — has begun aggregating travel data not just from airlines but from other types of providers of travel services, more for market research and targeting than for pricing purposes: “Increase the lifetime value of your customers with travel behavior data from Vistrio“.

The capabilities now being offered to marketers by Acxiom’s joint venture Vistrio — correlating travel records with other commercial records and profiles of individual consumers/travelers — would appear to be similar to those used in the (illegal) attempts to match JetBlue PNR data with Acxiom records in 2003. But while Vistrio has kept a low profile, and refuses to divulge its client list, it appears to have access to a smaller subset of airline PNRs than either Airline Automation or ARC.

In the past, Airline Automation (now Amadeus Revenue Integrity) has been the government’s first choice for normalized multi-airline, multi-CRS travel data. For those PNRs in its system, it has even more data than ARC, since Airline Automation get entire PNRs, not just ticketing records. On the other hand, because tickets have to meet IATA standards, while there are no standards for PNRs as such, aggregators are much better at normalizing ticket records than other PNR components.

In late 2001, well-known airline IT consultant R.W. Mann (who has served as an outside director and worked on other joint projects with Airline Automation), conducted “terrorist threat” profiling experiments with data from slightly more than 5 million PNRs of real travelers on an unknown number of airlines obtained from Airline Automation, as was revealed in this report (see page 28 of the PDF, numbered as page 23) and later confirmed by Mann in an interview with travel journalist and Identity Project consultant Edward Hasbrouck.

In mid-2002, Airline Automation was the conduit through which more than a million American Airlines PNRs were transmitted to the TSA and to four corporate consortia competing for the contract for the airline passenger surveillance, profiling, and control scheme then known as CAPPS-II and later renamed Secure Flight. AA and AirAuto pointed fingers at each other in dueling press releases about the terms of their agreements regarding the data, but both admitted that the data had been turned over, and there’s no record that either ever sued the other over it. (Other airlines were also involved, but AirAuto didn’t name names and unlike AA the other airlines didn’t confess, so we still don’t know which they were.)

But not all airlines contract with Airline Automation for PNR processing, so its PNR set is incomplete. ARC only processes payments for tickets issued by travel agents, not those sold directly by airlines, but has data for almost all tickets issued by agents in the USA for more than 170 airlines around the world.

The other major reason the government might prefer to get travel data from ARC, rather than from a CRS — or, perhaps, rather than a CRS division or joint venture such as Airline Automation (Amadeus) or Vistrio (Sabre) — would be to avoid potential liability for violations of the Wiretap and/or Stored Communications Acts. Particularly with respect to their travel agency subscribers, CRSs are unquestionably providers of “electronic communications services” and/or “remote computing services” — probably both. In United States v. Mullins, 992 F.2d 1472, 1478 (1993), the 9th Circuit took for granted that the Sabre CRS was acting as an “electronic communications service provider” when it transmitted travel agency PNR entries to airlines. We believe that the 9th Circuit was undoubtedly correct, and that disclosure of CRS messages and PNR data without proper authorization violates the Wiretap Act and/or the Stored Communications Act.

The implication is that CRSs that collaborated in the government’s post 9/11 programs of warrantless travel surveillance and “voluntarily” turned over PNR data to the government, without a legally valid demand, face the same potential liability to their customers — in the case of CRSs, that means travel agent subscribers — as the telecom companies that collaborated with the government’s warrantless telephone and Internet surveillance.

The difference is that Congress hasn’t (yet) immunized travel companies for their role in government spying, and that unlike people who have a hard time proving that the government listened to their phone calls or read their e-mail, CRS customers can easily prove that their communications have been turned over to the government, by obtaining copies of their PNRs from the DHS under the Privacy Act. It’s not a state secret, or a secret at all; the government has admitted and confirmed it. All this means that the CRSs are in much more extreme and potentially bankrupting legal jeopardy than the telecom companies, were they to be sued under the Wiretap and/or Stored Communications Acts. They are keeping their fingers crossed that nobody will notice the legal implications of their actions, but they’re not so stupid as not to realize that they’ve acted far outside the law. By now, we suspect that they are more than a little nervous, and reluctant to go any further without better legal cover. Their response to government requests for data has likely changed, although we don’t know when the change took place, from, “How can we help?” to “Can you give us some paperwork we can cover our ass with?”

(It’s also worth noting that the status of CRSs as electronic communications service providers also means that they would be subject to the data retention mandates of the proposed Internet SAFETY Act, if it is approved. That could be a mixed blessing, since it would require retention of records that could identify CRS users — including, ironically, CRS users from government surveillance agencies, no record of whose PNR queries is currently retained by CRSs for more than a few days.)

It’s less clear, but their ownership by and integration with their CRS parents might make Airline Automation (Amadeus) and Vistrio (Sabre) similarly vulnerable. As a company owned by airlines rather than a CRS, and much less likely to be found to be an electronic communications service or remote computing service (although either is at least arguable, and it’s hard to see how ARC would be subject to “national security letters”, as reported by Wired, except in the capacity of an electronic communications service provider), ARC is a legally safer channel through which the government can get much, if by no means all, of the same information.

Safer doesn’t mean safe, though. ARC may not have broken the law by giving PNR data to the Feds without a proper wiretap order (if it isn’t deemed to provide an electronic communications of remote computing service), but airlines and their agents who provided that data to ARC without adequate data protection covenants may well have violated the laws in the foreign countries where they are based, including Canada and the European Union. “Travel agent” isn’t just a label, but a description of a legal relationship. When a travel agent in the USA (or anywhere else) issues a ticket validated by an airline based in the EU, the principal in the transaction is that airline. And in acting as the agent of an EU airline, and executing contracts on its behalf, the agent in the USA or anywhere else is required to observe the same laws — including EU data protection laws — as apply to that airline as an EU-based legal entity.

It’s not U.S. travel agents’ fault that they violate the data protections laws of EU jurisdictions almost every time they issue a ticket for an EU-based airline, by sending personal PNR information to third-party contractors who can’t guarantee that it won’t be improperly passed on to government agencies. Airlines make no attempt at all to educate travel agents about their data protection obligations, although that ought to be one of the most important tasks for the chief privacy officer of a airline based in a country with more stringent data protection rules than those the USA, but which has appointed tens of thousands of agents empowered to act on its behalf and in its name in the USA. (For what it’s worth, that appointment of agents in the USA is also handled, in most cases, through ARC, in addition to ARC’s role as a financial clearinghouse.) And the CRSs and other intermediaries like ARC, on which travel agents depend, haven’t bothered to put in place the systems that would be needed for it to be possible for U.S. agents to comply with EU law. Nevertheless, it’s only a matter of time before someone notices that the emperor has no clothes, and challenges an EU airline on its home turf for the failure of its U.S. agents to follow EU data protection law.

did you know that bob mann is personal friends, a current consultant to, and both a former board member of and business partner of the guy who founded AAI?

Pingback: Tuesday, October 6 2009 « The Jeff Farias Show

Pingback: Friday, January 8, 2010 « The Jeff Farias Show

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » Travelport becomes first CRS to claim it complies with EU privacy law

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » TSA wants airlines to “share” frequent flyer records

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » Accurint exposed as data broker behind TSA “ID verification”

“Based on a Vague Tip, the Feds Can Surveil Anyone: Low-level “assessments” allow the FBI to follow people with planes, examine travel records, and run subjects’ names through the CIA and NSA.”

(by Cora Currier, The Intercept, January 31, 2017)

https://theintercept.com/2017/01/31/based-on-a-vague-tip-the-feds-can-surveil-anyone/

Pingback: FBI enlists reservation services to spy on travelers – Papers, Please!